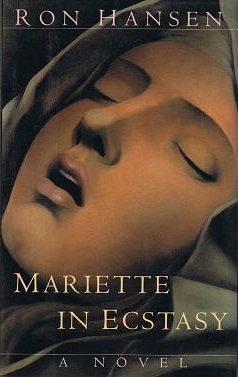

My pastor recommended Mariette in Ecstasy (1991) by Ron Hansen. He’d read it a few times. I borrowed it from the library and finished it in a few hours.

Mariette is the story of the young, beautiful postulant Mariette Baptiste, whose entry into the Sisters of the Crucifixion is distinguished by ecstasy and stigmata, all while contrasting a backdrop of doctrinal rigidity.

The book is laid out like a historical content analysis and oral history of a convent’s records. As a foundation, we see all the convent’s members and their ages, the agenda of their typical day, and the rules. We are privy to the storyline through different perspectives, interviews, letters, and objective scenes (appropriately made objective when the lens of rationality is applied). Sections within each part of the book are divided by red letter days.

Ostensibly, a central question in Mariette asks, Is she or is she not enduring an authentic spiritual experience? But this question only pertains to the plot between the characters, whose attempts to reconcile spirituality and rationality vary typically—skeptical, hateful, shifting, duplicitous, open, and worshipful.

Still, whether Mariette is experiencing ecstasy or stigmata ultimately does not matter. The overarching question is not posing spirituality against rationality. Instead, the central question is, How do households, institutions, and societies respond when observable suffering is associated with divinity?

⚠️ Spoiler in the black box. Highlight to reveal text. ⚠️

Human beings operate in institutions of habit. Our households, institutions, and societies are built upon rigid doctrines in which things must flow correctly. When somebody appears to be suffering from something that could be divine, it stops the flow. People tend to react negatively, skeptically, or naïvely when confronted by painful expressions of faith because spiritual experiences become obstacles for the institutionalized protagonists. Spiritual ecstasy or agony goes against the grain, against the flow, against the status quo. Thus, Mariette is not a protagonist; she’s—ironically—the villain.

When her father, a doctor, examines her “wounds” at the convent, he informs the convent that they’ve been duped. Her religious babbling and spiritual claims are why he sent her to the convent in the first place. She was kicked out of her household. The sisters pack her belongings and kick her out too. In the epilogue, we read about a woman who holds onto her convictions despite her ghostly reputation around town. She hobbles about wounded, like Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye. To answer the red herring, ‘Is Mariette undergoing authentic spiritual experiences? The answer is no. We have to remember that Mariette wasn’t actually doing anything. Spiritual experience is not just associated with suffering but with meaningful acts of work that serve God’s kingdom beyond a cloister.

We do not set goals and solve them. We solve problems because these are the issues in the way of goals. Households, institutions, and society have goals, and they have problems. So, in answering the book’s central question, How do households, institutions, and societies respond when observable suffering is associated with divinity? Those who spiritually suffer are shunned because they do not move households, institutions, and societies toward their worldly goals; they are treated as ‘in the way.’ Whether someone presents divinity or a hoax, they are treated the same. And who can blame us? We have high standards for truth, which was seldom handed over in the Old and New Testaments. Tests, trials, and skepticism are precursors to vulnerable belief.

This book is a light, palatable read into a deep subject. It is beautifully written and painstakingly so—so much that it almost imitates the monotony of the convent. Admittedly, I skimmed through many of the descriptive scenes, as I felt many were unnecessary in telling the story. Still, Hansen writes a compelling story about faith, skepticism, and the fear of being wrong when we want to be right.

Leave a comment