I wrote this small research paper for a tutoring certification in CRLA (College Reading & Learning Association). My theory of choice is “Social Construction Theory,” which was the base theory for my graduate research on the social construction of specific animal welfare policies in Texas cities. The theory has broad applications, and I was excited to see its extensive use in the literature on writing and composition. Social Construction Theory explains how knowledge is not solely gained by individual observations but through complex social interactions. This paper is intended for tutors and college writing centers, but it is still helpful for writers like you. Feel free to leave a comment.

Rethinking the Audiences of College Writers

7 December 2022

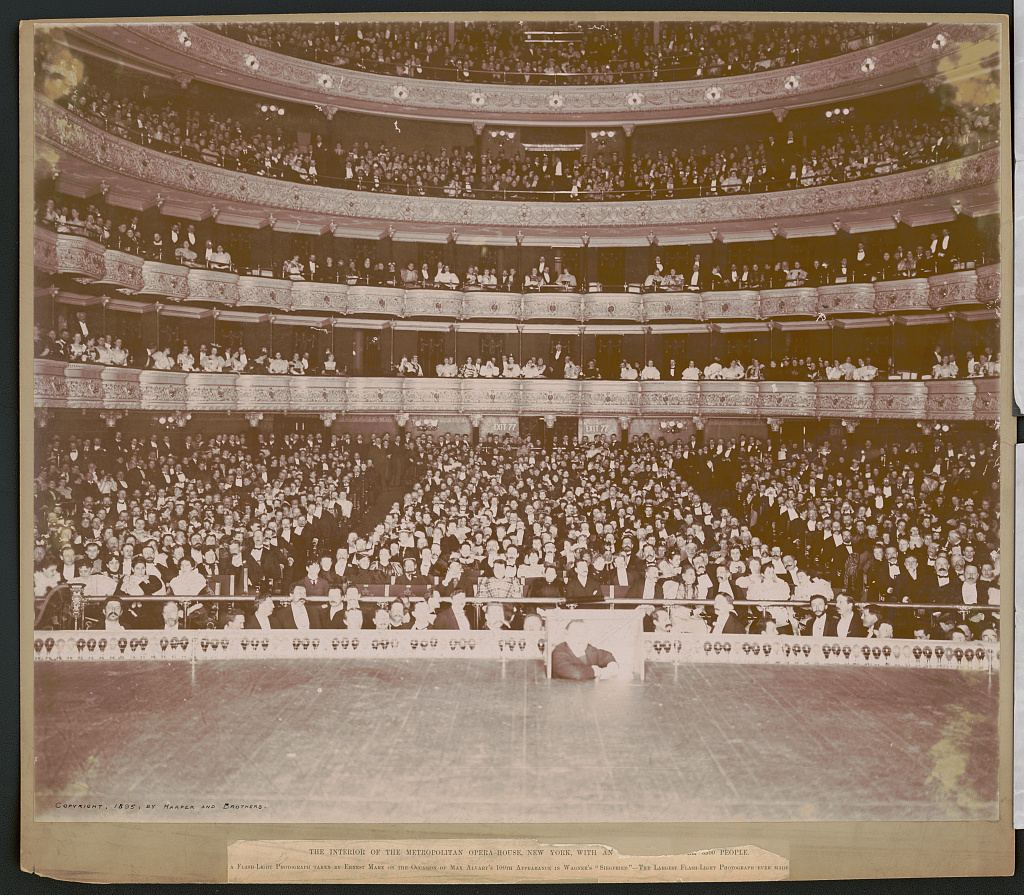

We find advice related to audience in websites, blogs, books, and workshops on writing. “Do you want to be a better writer? Know your audience,” they say. The problem with this advice is that most writers, especially college writers, might lack ideas about what audience means or what it could mean. Just hearing the word audience may invoke misconceptions—perhaps an auditorium of scholarly stereotypes or a stern, critical professor. At San Antonio College, where I am a writing tutor, I notice that some college writers write prolixly, and some struggle to write at all. Could the imagined gaze of real and mythical spectators produce these writing problems? My experience as a writer and a writing tutor inspires this research paper, in which I ask how audience factors into a college writer’s efforts. I answer this question through a brief literature review and primary experience, arguing that the reconceptualization of audience is necessary for college writers and as crucial to skillful writing as mastering the rhetorical elements in their compositions.

Rethinking audience requires us to visit a body of literature that spans the 1970s to the 1980s (Ede, 1984), when composition theorists questioned theoretical communication models, e.g., sender, receiver, information, feedback, and noise. In his seminal paper, “The Writer’s Audience is Always a Fiction,” Walter Ong (1975) observes that when “we put aside this alluring but deceptively neat and mechanistic mock-up and look at verbal communication in its human actuality… problems with the writer’s audience begin to show themselves” (p. 10). Unlike most speakers, writers seldom see their audience, relying on imagined audiences instead. Some writers do this well, and some writers do not, a difference that is made clear in the experimental research of Flower and Hayes (1980), who found that what separates good writers from poor writers could be in—among other skills—their conceptualization of audience and how the writers went about reaching them. Furthermore, Berkenkotter (1981) found that rich representations of audience “played a significant role in the development of the writer’s goals” (p. 395); Rubin (1984) found that good writers anticipate audience reaction, using an array of subskills to infer potential readers; and Cohen and Reil (1989) found that the quality of student writing was improved when the goal was “to communicate with their peers as compared to when they wrote to demonstrate their skill for their teacher’s evaluation” (p. 155).

In hindsight, the theorists from this era were the wellspring for a new way of thinking about audience. To them, writers were simultaneous agents and objects of influence (Rafoth, 1988), and audience referred to the process behind writing, a collectivity based on inherent conversationality in which “every bit of writing qualifies as an entry into a universe of discourse” (Rubin, 1988, p. 16). In other words, audience was not synonymous with receiver; audience was the relationship of senders and receivers—a conversation from which both writers and readers emerged and from which quality writing was produced. Writers, especially college writers, do not just come from nowhere and arrive at the admissions office; college writers come from audiences that house the relationships that shape their identities, knowledge, and reality.

However, sometimes a student’s problem is not a lack of audience; instead, it is the persistence of an unhelpful audience, especially one that is judgmental or illusory. Such audiences can negatively influence the writer and the final product. Take this paper, for example, in which I imagined an English professor, my fellow writing tutors (judgmental audiences), and the editors and readers of the Writing Lab Newsletter (illusory audiences). Both kinds of audiences shaped this paper, but so did their absence. While drafting, I tuned these audiences out, freeing myself of their gravity. I am not alone in making audiences disappear, nor do I have reasons why. Likewise, in explaining that he sometimes closes his eyes while writing, Peter Elbows (1987) wrote:

An audience is a field of force. The closer we come—the more we think about these readers—the stronger the pull they exert on the contents of our minds. The practical question, then, is always whether a particular audience functions as a helpful field of force or one that confuses or inhibits. (p. 51)

What Peter Elbows is getting at is how a writer’s social construction of audience can have positive and negative effects on the writing process. Sure, audience awareness can improve the overall quality of students’ writing, but audience awareness is less effective for drafting students than for revising students (Roen & Willey, 1988). As writing tutors, we should sometimes help students free themselves of audience so that they can free their expression, get ideas down, and convey meaning through an inherent voice. In doing so, the tutor would work with the student’s pure sense of writing rather than prose influenced by notions of academia.

This research suggests that—for all writers—there is a time for audience and no audience because we can better understand audience by acknowledging what it is—a mental fabrication even when concrete facts about the audience are known. “The historian, the scholar or scientist, and the simple letter writer all fictionalize their audiences, casting them in a made-up role and calling on them to play the role assigned” (Ong, 1975, p. 13). Therefore, the concept of audience—concrete or socially constructed—poses special considerations for college writers and their tutors. If the tutor believes that the tutee is dealing with a problem of audience in a revision phase, they could ask, ‘Who is this writing for; why do you think so; and who else could read this?’[1] However, if the tutor believes that the tutee is dealing with a problem of audience in a drafting phase, the tutor could try to eliminate the audience from the tutee’s mind, e.g., asking the student to conversate through their idea with the tutor before trying to compose it. By keeping an open mind to audience problems, a tutor may find that a tutee’s rhetorical and compositional issues stem from this macro-level issue.

The reconceptualizing of audience could be the key to reminding the student to think about their writing in more significant terms—like a batter swinging for the fans in the bleachers and not for the pitcher who threw the prompt; the readers in the distance and not for the instructor in the classroom; or, sometimes, just for themselves when no one is looking. By rethinking audience, a tutor can empower students to reimagine their written expression and, above all, themselves.

References

Berkenkotter, C. (1981). Understanding a Writer’s Awareness of Audience. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/356601

Cohen, M., & Riel, M. (1989). The Effect of Distant Audiences on Students’ Writing. American Educational Research Journal, 26(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163029

Ede, L. (1984). Audience: An Introduction to Research. College Composition and Communication, 35(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.2307/358092

Elbow, P. (1987). Closing My Eyes as I Speak: An Argument for Ignoring Audience. College English, 49(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/377789

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1980). The Cognition of Discovery: Defining a Rhetorical Problem. College Composition and Communication, 31(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/356630

Ong, W. J. (1975). The Writer’s Audience Is Always a Fiction. PMLA, 90(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/461344

Rafoth, B. A., & Rubin, D. L. (Eds.). (1988). The Social Construction of Written Communication (Illustrated) [Book]. Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Roen, D. H., & Willey, R. J. (1988). The Effects of Audience Awareness on Drafting and Revising. Research in the Teaching of English, 22(1), 75–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40171133

Rubin, D. L. (1984). Social Cognition and Written Communication. Written Communication, 1(2), 211–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088384001002003

Rubin, D.L. (1988). Introduction: Four Dimensions of Social Construction in Written Communication. In Rafoth, B. A., & Rubin, D. L. (Eds.). (1988). The Social Construction of Written Communication (pp. 1–33) (Illustrated) [Book]. Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Rafoth, B. A. (1988). Discourse Community: Where Writers, Readers, and Texts Come Together. In Rafoth, B. A., & Rubin, D. L. (Eds.). (1988). The Social Construction of Written Communication (pp. 131-146) (Illustrated) [Book]. Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Zackery, S. M. (2014). Musical Missteps: The Severity of the Sophomore Slump in the Music Industry. Scripps Senior Theses, Paper 335. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/335

[1] adapted from Visual Thinking Strategies, see https://www.artmuseum.org/art-suitcase/why-ask-questions/ for more info

Photo Credit: “The interior of the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, with an [audience of over] 3,500 people A flash-light photograph taken by Ernest Marx on the occasion of Max Alvary’s 100th appearance in Wagner’s “Siegfried” – The largest flashlight photograph ever made.” 1895. The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004678715/

Leave a comment